“The countenance is the portrait of the soul, and the eyes mark its intentions.” – Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC)

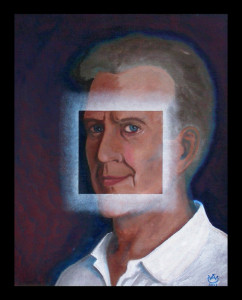

Face 2 Virtual Face with my forebears; and myself at age 60. The fascination with portraiture up-close was stimulated by this self-portrait painted in 2003, in which I experimented with altering the impact of the painting by adding the device of the illuminated square. This refocuses the art from a time-specific depiction of myself with clothes and hairstyle reflecting the times I live in (although they are still there), to a singling out of the inner mask consisting of eyes, nose and mouth, which is much more timeless. Although I had done other self-portraits over the years – mostly drawings- this was my first In Your Face depiction. The experiment ultimately prompted a deeper understanding of persona, my own, and others; it also encouraged me to delve creatively through art, particularly photography, into the variety of masks we wear throughout our lives. “All the world’s a stage…”

Face 2 Virtual Face with my forebears; and myself at age 60. The fascination with portraiture up-close was stimulated by this self-portrait painted in 2003, in which I experimented with altering the impact of the painting by adding the device of the illuminated square. This refocuses the art from a time-specific depiction of myself with clothes and hairstyle reflecting the times I live in (although they are still there), to a singling out of the inner mask consisting of eyes, nose and mouth, which is much more timeless. Although I had done other self-portraits over the years – mostly drawings- this was my first In Your Face depiction. The experiment ultimately prompted a deeper understanding of persona, my own, and others; it also encouraged me to delve creatively through art, particularly photography, into the variety of masks we wear throughout our lives. “All the world’s a stage…”

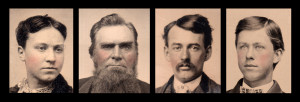

Recently this fascination has been revived; post my June sojourn in Dayton I’ve been taking a better look at the photographic record archived somewhat haphazardly by my family in Maine; a record that friends have reminded me is quite unusual, as well as extensive. From those archives I borrowed a number of albums, large and small, dating from the late 1800s. My plan is to scan and catalog them, putting together as complete an electronic record as possible while the images are still in reasonably good condition. Above, three consecutive pages (featuring the same four individuals) from an album owned by my great-grandmother Isabelle Pierson Hurd [Waterhouse] (Feb 14, 1852 – Oct 6, 1890), which measures 1-3/4″ high by 3-3/16″ wide. The time period covered by the album is the mid-1870s, probably before her marriage at age twenty-seven in 1879. The album accommodates postage-stamp-size tintypes that measure 1″ high by 3/4″ wide on average. However, there is no standard; all of them were obviously hand-cut from the tin, none of them are exactly the same size, nor are they perfectly square-cut, as if by machine. Being reminded by my friend Arthur Ostroff recently that tintypes reserve reality, I flip-flopped the images after the initial process of scanning them at 1200 dpi, lightening dark exposures, heightening contrasts, cleaning up excess ‘noise’ particularly where it distorted a face, enlarging the images, eventually cropping them to downplay the details of clothing and background. All this in order to take a better look at these forebears from the Hurd/Waterhouse side of my family…

Recently this fascination has been revived; post my June sojourn in Dayton I’ve been taking a better look at the photographic record archived somewhat haphazardly by my family in Maine; a record that friends have reminded me is quite unusual, as well as extensive. From those archives I borrowed a number of albums, large and small, dating from the late 1800s. My plan is to scan and catalog them, putting together as complete an electronic record as possible while the images are still in reasonably good condition. Above, three consecutive pages (featuring the same four individuals) from an album owned by my great-grandmother Isabelle Pierson Hurd [Waterhouse] (Feb 14, 1852 – Oct 6, 1890), which measures 1-3/4″ high by 3-3/16″ wide. The time period covered by the album is the mid-1870s, probably before her marriage at age twenty-seven in 1879. The album accommodates postage-stamp-size tintypes that measure 1″ high by 3/4″ wide on average. However, there is no standard; all of them were obviously hand-cut from the tin, none of them are exactly the same size, nor are they perfectly square-cut, as if by machine. Being reminded by my friend Arthur Ostroff recently that tintypes reserve reality, I flip-flopped the images after the initial process of scanning them at 1200 dpi, lightening dark exposures, heightening contrasts, cleaning up excess ‘noise’ particularly where it distorted a face, enlarging the images, eventually cropping them to downplay the details of clothing and background. All this in order to take a better look at these forebears from the Hurd/Waterhouse side of my family…

Taking a better look at the depicted three pages from the album, I found it interesting to note that the first shows my great-grandmother Isabelle beside her father Dr. Eben Hurd (1816-1895). She’s on the left facing toward the spine of the album, looking away from him (unlike the corrected images immediately above). On the back of that page are two men: on the left Isabelle’s future brother-in-law William Henry Waterhouse, and on the right her betrothed, James Nason Waterhouse (1849-1931), my future great-grandfather. The third page has duplicates of the tintypes of her and James N, facing towards each other – a rather touching way of depicting the transition she was about to experience as a new wife leaving her father for a husband. Please note in the above montage of four images how much more involving are the portraits of Eben and William, the two men in the middle looking directly at you the viewer; as opposed to the outside images of Isabelle and James, who are looking elsewhere, not making eye contact with the viewer. More on this theme below…

Taking a better look at the depicted three pages from the album, I found it interesting to note that the first shows my great-grandmother Isabelle beside her father Dr. Eben Hurd (1816-1895). She’s on the left facing toward the spine of the album, looking away from him (unlike the corrected images immediately above). On the back of that page are two men: on the left Isabelle’s future brother-in-law William Henry Waterhouse, and on the right her betrothed, James Nason Waterhouse (1849-1931), my future great-grandfather. The third page has duplicates of the tintypes of her and James N, facing towards each other – a rather touching way of depicting the transition she was about to experience as a new wife leaving her father for a husband. Please note in the above montage of four images how much more involving are the portraits of Eben and William, the two men in the middle looking directly at you the viewer; as opposed to the outside images of Isabelle and James, who are looking elsewhere, not making eye contact with the viewer. More on this theme below…

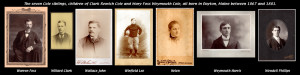

On the Cole side of the family I recently compiled a montage of the seven siblings – six sons and one daughter – that includes my

On the Cole side of the family I recently compiled a montage of the seven siblings – six sons and one daughter – that includes my

grandfather as the sixth. These early printed-on-paper images all date from the 1890s and 1900s.

grandfather as the sixth. These early printed-on-paper images all date from the 1890s and 1900s.

Wanting to take a better look, I cropped them down to close-ups, then strung them together. Taking it the next step further, I created an image that brings home the power of direct eye contact. The first six individuals are not making eye contact with the camera, although in some cases it almost appears that way – they seem to be looking just behind the photographer’s head at some indefinite spot. However, the last person, Wendell, is looking right back at the camera – eye to eye. With the first six the viewer is merely an observer; with the seventh, there is engagement, connection between viewer and viewed. There’s great power in that communication, which separates mediocre dated portraiture from outstanding timeless portraiture, which is ART, whether the medium is painting or photography.

Wanting to take a better look, I cropped them down to close-ups, then strung them together. Taking it the next step further, I created an image that brings home the power of direct eye contact. The first six individuals are not making eye contact with the camera, although in some cases it almost appears that way – they seem to be looking just behind the photographer’s head at some indefinite spot. However, the last person, Wendell, is looking right back at the camera – eye to eye. With the first six the viewer is merely an observer; with the seventh, there is engagement, connection between viewer and viewed. There’s great power in that communication, which separates mediocre dated portraiture from outstanding timeless portraiture, which is ART, whether the medium is painting or photography.

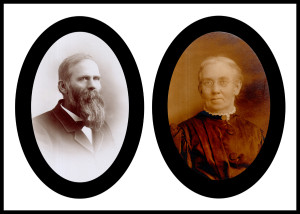

One of the earlier projects that got this ball rolling was putting together a montage showing the aging of my great-grandfather Clark

One of the earlier projects that got this ball rolling was putting together a montage showing the aging of my great-grandfather Clark

Remich Cole (Jan 1, 1841 – Jan 21, 1915) starting with a portrait taken in April 1861, when he joined the Civil War at age 20

Remich Cole (Jan 1, 1841 – Jan 21, 1915) starting with a portrait taken in April 1861, when he joined the Civil War at age 20

immediately after the war started; followed by portraits from approximately 1867, 1874, 1881, 1900 – tracing his youth through maturity post sixty as a successful but hard-working farmer in Dayton, Maine. At left, the eldest known portrait of Clark combined with the only known photographic portrait of his wife, Mary Foss Weymouth [Cole] (Jan 14, 1849 – Apr 9, 1937). Her portrait is hard to pinpoint in time considering her age and dress. My guess is that the portrait was taken in her latter years, possibly after Clark’s death in 1915; she died in 1937, outliving him by twenty-two years. For the occasion she may have donned an elegant older dress in her possession from the previous century; intent on looking her best for posterity.

immediately after the war started; followed by portraits from approximately 1867, 1874, 1881, 1900 – tracing his youth through maturity post sixty as a successful but hard-working farmer in Dayton, Maine. At left, the eldest known portrait of Clark combined with the only known photographic portrait of his wife, Mary Foss Weymouth [Cole] (Jan 14, 1849 – Apr 9, 1937). Her portrait is hard to pinpoint in time considering her age and dress. My guess is that the portrait was taken in her latter years, possibly after Clark’s death in 1915; she died in 1937, outliving him by twenty-two years. For the occasion she may have donned an elegant older dress in her possession from the previous century; intent on looking her best for posterity.

“Sensitive people faced with the prospect of a camera portrait put on a face they think is the one they would like to show to the world… Every so often what lies behind the facade is rare and more wonderful than the subject knows or dares to believe.” – Irving Penn (1917-2009)

{ 0 comments… add one now }